Social media are often discussed as a kind of force of nature that can shape, change, and destroy entire societies. This deliberately overlooks the fact that social media are a part of society – created out of a field of tension between social, economic, and political interests, and therefore as much a product of society as society has become a product of social media. Understanding this will not only allow us to better discuss issues like “TikTok and our children,” but also to think about alternatives to Big Tech, as Aileen Derieg argues.

*

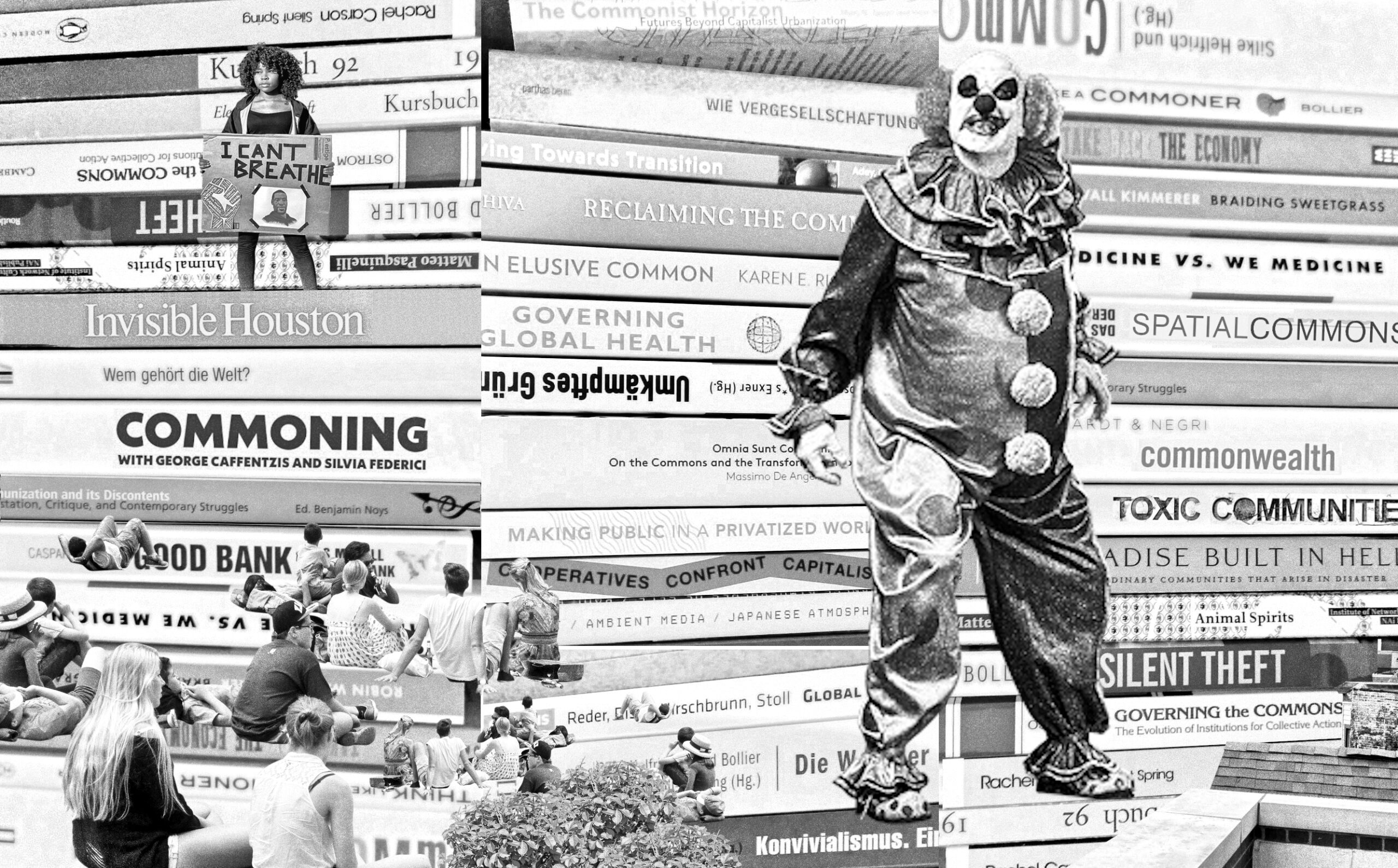

Recent years have seen a growing body of works critically investigating the influence of corporate internet services, platform capitalism, data mining, privacy, and surveillance. In his book “The Internet Con – How to Seize the Means of Computation,” for instance, Cory Doctorow traces the rise of Big Tech monopolies and their detrimental effect on society, but also describes how users end up trapped within platforms they are unhappy with. In “The Road to Nowhere” Paris Marx draws parallels between the development of car culture leading to complete automobile dependency and the Big Tech monopolies that seek to crush alternatives. The economic, political, sociological and psychological impacts of internet technologies are currently being critically scrutinized by academics, journalists, and activists, while artists, activists and hackers seek to develop alternatives.

Against this backdrop, the day-long Transversal workshop “Publishing and Becoming-Public After Social Media” on March 19, 2024 in Vienna offered a philosophical perspective, thus opening up an expanded view of social media, subjects, and society.

While Stefan Nowotny proposed three very short excerpts from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Christian Marazzi, and Giuseppina Mecchia, revisiting Nowotny’s own essay “The Condition of Becoming Public” from 2003 turned out to be even more illuminating. At that time, he wrote in reference to “the clandestines,” “the sans-papiers”: “it is a matter of becoming-public, that does not simply consist of the transition from a ‘not-being-public’ to a ‘being-public’ (from invisibility to visibility, from non-representation to representation), but rather of opening up a collectivity in the in-between spaces of representation, which inter-venes – literally – in public life as a social becoming.”

Are social media to blame?

For more than twenty years social media have been defining us more and more “granularly” as “target groups”, ostensibly to serve us with information that interests us, but actually to sell fine-grained data sets to data brokers. Content is irrelevant; all that counts are milliseconds of attention, during which advertisements can be shown. Ticking off all the boxes to identify gender, geographic location, ethnicity, or any other demographics does not result in visibility or representation, but only higher priced data sets. This has been analyzed and discussed at length and in many places in the meantime, but the first discussion of the workshop ended up being about how to politicize “becoming-public,” which seems most urgently needed now.

Considering social media through the lens of the writings of Immanuel Kant, Karl Marx, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Louis Althusser and others opened up different perspectives for me, as I usually focus more on the technological side. One example is the concept of interpellation: According to Althusser, state apparatuses such as the family, the school, the police, and the mass media, tell individuals from infancy what they are in terms of class, gender, race and other identities – an act of interpellating someone through labels that implies that we learn to respond to those labels. This concept seems especially useful here for moving beyond the conventional hand-wringing considerations of the influence of TikTok and Instagram on young people’s self-image.

In another input text recommended by Felix Stalder, Shusha Niederberger writes: “In his view, the subject does not exist independently of its surroundings, but is created and sustained (hailed) through calls of institutions (Althusser et al.), and in the context of this text: infrastructures. … [T]he process of infrastructural interpellation is not a deterministic process, but operates in relation to other callings, self-understandings, and already established subject positions.” A subject created and sustained through interpellations of institutions and infrastructures is a different social imaginary than an inexperienced teenager in danger of manipulation. Removing the opportunity to blame social media for the unhappiness of young people returns the responsibility to where it belongs: society as a whole with all of its educational, political, cultural and other institutions.

Identity checkboxes vs. server options

In the same text by Shusha Niederberger, she also goes on to examine how the process of signing up for Mastodon differs from making an account on Twitter in ways that confused and irritated many people who fled to Mastodon after Elon Musk took over Twitter. While commercial social media platforms presuppose a self-contained liberal individual, who identifies themselves by choosing predefined attributes from drop-down menus or boxes, Mastodon first asks new members to choose a server.

In 2022 AMRO – Art Meets Radical Openness, a small biennial festival in Linz, Austria, organized a panel discussion titled “Hosting With The Others,” bringing together system administrators from some of the old “art servers” from the late 1990s and activists from a new wave of community servers and self-hosting, including the expanding practices of feminist servers. After so many years of the walled gardens of commercial social media, it seems there is a growing interest in independent servers, but there also seems to be a widespread need for explanation of what a server actually is. On the one hand, focusing attention on the machines that enable connectivity returns a level of materiality to the discussion of social media. On the other hand, however, independently operated self-hosted or community servers require a different way of thinking. This means questioning assumptions about being “always on,” always available; it means an awareness of the actual, real human beings who care for the machines and who sometimes need to eat or sleep or just take a walk. Connectivity then is not just an abstract concept, but a set of concrete actions.

As Shusha Niederberger writes, for people accustomed to being hailed as individuals, it can be confusing to be confronted with having to choose a community as the first step. In addition, Mastodon is not a monolithic centralized platform like Twitter, but rather a multitude of small to mid-sized interconnected “instances.” And it is not even the whole “Fediverse” (“a collection of social networking services that can communicate with each other (formally known as federation) using a common protocol”), but rather only one way to connect with other federated instances like Pixelfed or PeerTube.

When mainstream media continue to refer to Mastodon as a “Twitter alternative” (e.g. CNN: “A beginner’s guide to Mastodon, the Twitter alternative that’s on 🔥”, or TechCrunch: “A beginner’s guide to Mastodon, the open source Twitter alternative”) and compare the advantages and disadvantages of these two alternatives, it obscures that the fact that the Fediverse is not only different from commercial social media because it is free of advertisements. The underlying ActivityPub protocol is more closely akin to email and reflects an approach more like interconnected communities and collectives rather than linking isolated and atomized individuals to one another. What makes Mastodon interesting is not that it offers a haven from the toxic environment of Twitter, but rather that the Fediverse offers a way of becoming public that counters capitalist individualistic subjectivation, and subjects already embedded in communities have possibilities for agency beyond the predefined attributes of “target groups.”

Towards “federating” knowledge

Somehow, the spirit of the Fediverse was mirrored in the format of the workshop “Publishing and Becoming Public After Social Media.” Inviting six knowledgeable people from different fields to recommend short texts or excerpts of texts by other knowledgeable people, was a welcome departure from the conventional format of panel discussions, where individual experts present themselves and their own work. Perhaps this form of collaborative reflection might even be considered as a way of “federating” knowledge. In light of the trajectory from corporate social media platforms to TESCREAList visions of a dystopian future, resistance is not solely a technical question, but also requires critical philosophical reflection.

Note from the editors: The author of this text participated in the workshop “Publishing and Becoming Public After Social Media” organized by Transversal as part of the series Peripheral Visions.